by Megan McSweeney

Loi Dang-Nguyen is the English as a second language and foreign language learning specialist in the Akron Public Schools. For her, the job is personal. Coming from Vietnam in the ‘70s, she and her family were some of the first refugees to be resettled in Akron.

“My goal is to make sure that our refugees and immigrants do have access so that they will continue to excel,” Dang-Nguyen said.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, all school-aged children have a right to public education, regardless of immigration status. Lacking documents, such as birth certificates and social security cards, cannot bar a student from enrolling in a public school.

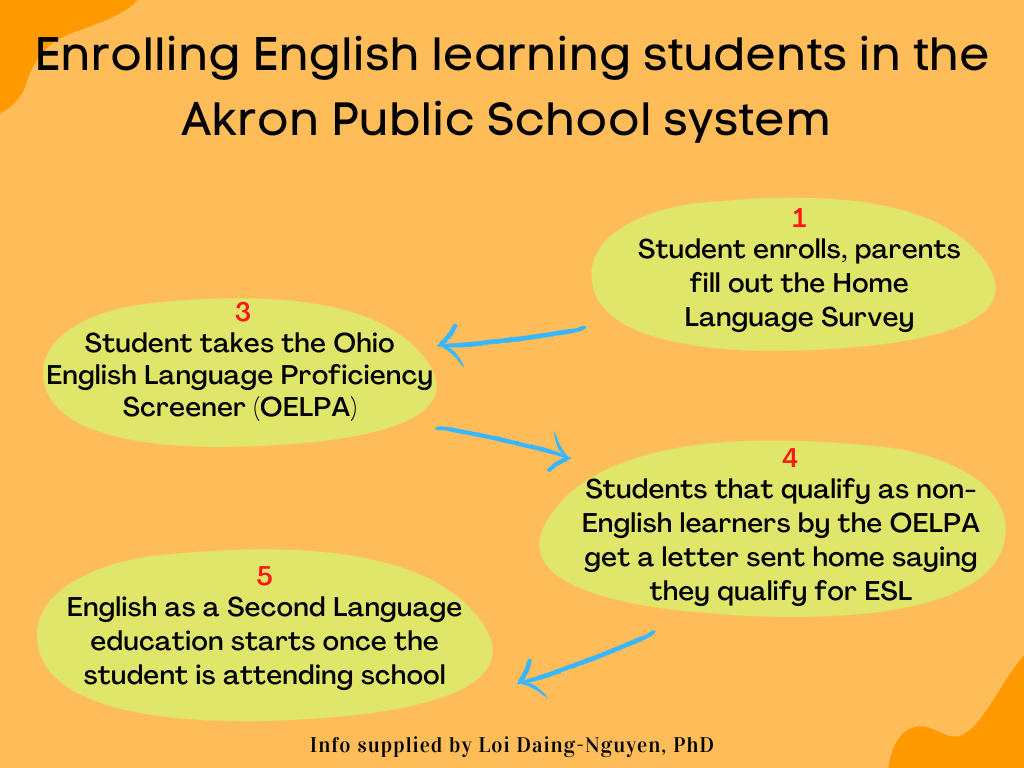

Enrolling resettled students is not hard. In Akron, student enrollment is available online, so parents can go through the enrollment process with their caseworker who can aid them in the application process. They also have the option to use the school system’s engagement center, where an interpreter will sit with the families and work one-on-one with them through the enrollment process.

Students with no transcripts or gaps in their education usually get placed in the grade that aligns with their age instead of their level of education. While sometimes the students are on track from the start, students with a gap in their education may be placed a year below, after the school discusses their options with the parents.

“We put in our recommendation a placement below [grade level] or based on the parent asking if they can place them a year below,” said Dang-Nguyen.

Noorulbari Afghanmal, a translator and tutor with APS, said that this is where some of the students begin to struggle.

“Some of the students coming in may be in sixth grade age-wise, but they have no former education from their home country. What really helps them, with learning English especially, is the total immersion in the classroom. When I’m talking to them in their native language, I may be using words that they wouldn’t know because it is academic language. So they’ll pick it up in English anyway since it is the first time they are being taught a certain concept.”

Noorulbari Afghanmal

He said that younger students, like from kindergarten to second grade, pick up English in a matter of months. It is the older students in middle school and high school that take more time to learn.

In regards to growth, Afghanmal said it may be that students whose parents attended school in their home country are encouraged to do well in school, as opposed to those who may be the first people in their immediate family to attend school. “When you look at two year growth between a student that is doing well and another who is not, there is no formal research but I feel the parents’ education may be a factor,” he said.

Like their American-born peers, there is no one thing that all students struggle with when it comes to learning.

“One may be better at language arts and struggle with math, where another has a hard time with science but loves math,” he said.

Similarly, resettled children may have American-born classmates who are placed in classes they are not succeeding in.

“Language barrier and academic demands, not just for resettled students but in our schools, we don’t have kids reading and working on grade level and we still put them on grade level,” Dang-Nguyen said. “So that is when we put in the support that is needed for the kid.” Tutoring is available after school, Dang-Nguyen said. But some students don’t take advantage of this opportunity. English classes for adults provided by the district also do not have high attendance rates because they are too busy working to support their families, she said.

So Dang-Nguyen has shifted some of the burden of helping refugee students to her staff. “Initially we did English classes with parents, but the enrollment was not very good,” she said. “So now we’re looking at professional development for our staff on cultural competency, and how to work with kids who have trauma who are refugee kids. So we are building up our teachers’ capacity to work with diverse learners.”

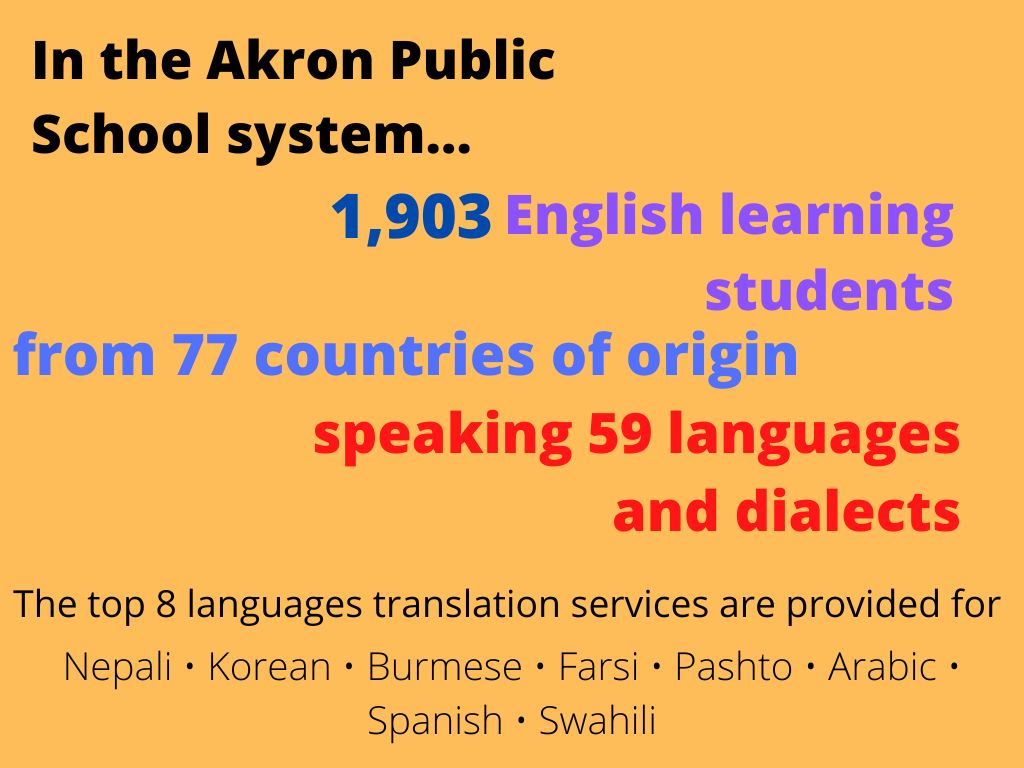

Students are also provided with interpreters, who are there to help when students get stuck on words or need help with directions. TESOL teachers, formerly known as teachers of English to speakers of other languages, are teachers who are certified to teach English to non-English-speaking students. Full-time teachers earn this certification on top of their teaching license, while part time teachers and tutors attend a monthly training where they are trained in the content through the curriculum specialist. The support is built into the students intervention plan.

Working as a translator in the schools is heavy work emotionally. Many of the students, especially the ones newly attending school recently, are coming in with trauma that they experienced in their home country. The translators are the only people they have in school that feel familia. Afghanmal said he will be called in to help console new students, or they will follow him to his next class room after his time with them is over for the day.

“Many of the kids coming in now are dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder because they experienced what we were seeing on TV and social media.”

Noorulbari Afghanmal

A majority of the tutoring is done in English, to help better their immersement, where translation work is used primarily when a student is stuck with instructions.

While individual student learning can’t be disclosed, the state has an English proficiency assessment that English learning students are required to take annually. The Ohio English Language Proficiency Assessment (OELPA) is a state test used to determine an English learner’s proficiency level and to exit from the English language program. Akron Public Schools had either met or exceeded the growth target for five consecutive years. “That gives us an idea what what we’re doing is working,” Dang-Ngyuen said.

The school system met or exceeded the state’s goal from 2016-2020. When COVID hit in March of 2020, 97% of Akron’s EL students had taken the OELPA, meaning, for the most part, the system’s overall score was not affected by the pandemic, and they reached their goal. The test is scored on a 1-5 scale student to student. A score of 1 means they are a beginner learner, a 5 shows they are an advanced learner. The school system is graded on what percentage is considered proficient based on their grade level, with a goal percentage set by the state.

“In 2021, we went down to 27 percent,” said Dang-Nguyen, “The target was like 60 percent and we hit closer to 20.”

There were a number of reasons: a good number of students didn’t take the test, and those that did had spent the past year and a half of online instruction on school-provided chromebooks, which is harder to follow for students still learning English.

“We translators were having to make these videos for students and their families on how to operate Google Meet and access homework, which was not a part of our job before,” Afghanmal said.

These videos were created in order to combat low-attendance rates due to a lack of technological know-how. The teachers shared an initial video, how to log into Google Meet, with students, and other issues are worked on as they came up. If a teacher noticed a student was struggling to log in, they told the interpreters, who then called the student’s home and talked them through how to log in, as well as troubleshoot other issues.

Now that school has returned to in person classes, Dang-Nguyen said that they are excited to see the students thrive again.

“We’re looking forward to seeing how our ‘22 data will be.” she said.