By Reegan Saunders

Rain pours behind stained glass windows past their prime. I sit in a church basement. The lighting is dim, and the room is plain but clean. There are a few round tables and a small screen with a projector.

The room is quiet until people begin to file in. Many of them are familiar with each other. “Jambo!” is exchanged warmly between the people who speak Swahili. Some dress in casual clothes, while others opt for traditional clothing. Laughter and chatter begin to fill the space.

As the adults are checking in (“What is your name?” “What is your phone number?” “Your email address?” “Have you taken the language test yet?”), coloring pages and snacks are passed around to the children. There is a language disconnect between the instructor in charge of check-in and the people around the room. The Swahili interpreter has not arrived yet, so he reads a list of terms he has been studying – welcome, daughter, address. People laugh at his misinterpretations, but they are kind and help correct him.

Welcome to America.

Akron, Ohio is one of the dedicated places for the United States’ refugee resettlement programs. Refugees in Akron come from all over the world, but often the city becomes home to people from Burma, Nepal, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Ukraine and Democratic Republic of Congo.

When refugees arrive in Akron, they are given a host of resources, but one of the essential ones is a cultural orientation run by the International Institute of Akron. The institute provides education services, employment services, social services, translation services, legal services and so much more.

But it cannot be enough.

Coming to America had caused more trauma and more struggle.

The orientation begins and it seems to be running as it should. Instructors stand at the front of the room and lecture on what has been deemed essential information for navigating life in Akron.

However, during one of the sessions, a father, accompanied by his two children, stood up. He wanted to ask a question via the interpreter. As he raced through his testimony, the Swahili interpreter tried to keep up, chasing his words in English for the rest of the group to understand.

This man arrived in America and had been given the expectation they would be placed in a town where his kids’ school would be within a mile of their home. A town where everything would be walkable and accessible. When they arrived in Akron, he found that his kids’ school was five miles away from their home, and the school bus would not reach their neighborhood.

He said that coming to America had caused more trauma and more struggle.

“Why do you think we are here today?”

Earlier in the orientation one of the instructors posed this question.

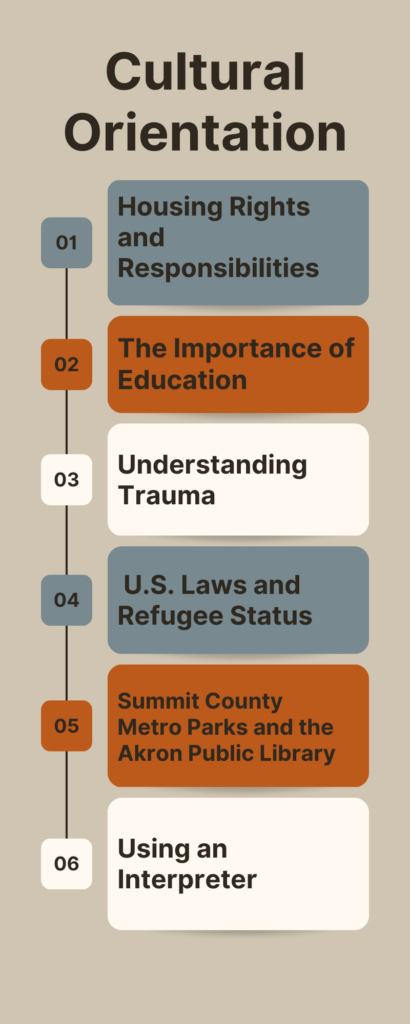

The cultural orientation focuses on a few pillars: housing rights and responsibilities, the importance of education and understanding trauma are all covered before lunch. After a break, it’s U.S. laws and refugee status, Summit County Metro Parks, the Akron Public Library and using an interpreter.

The consensus of the attendees– the orientation’s purpose is to help people understand the steps needed to acclimate to their new lives in Akron, the first step is learning English. As the instructor explained how speaking, reading and writing English was essential for working in America, for navigating their new lives, I thought to myself about how inaccessible America is for people who are not fluent in the language.

There are so many tasks we take for granted– buying groceries, sending emails, paying bills, answering phone calls, catching the bus. How do you navigate transportation if you can’t decipher left from right?

The International Institute of Akron offers month-long English classes – two times a week for a few hours; the courses are sorted by level of understanding, and the eventual goal is total fluency in speaking, reading and writing.

However, this system doesn’t work for everyone.

On one end, with school, jobs and other commitments, the class does not have a space in people’s schedules. On the other end of the spectrum, the class is simply not enough. During the orientation, one man via interpreter asked if there were opportunities for more immersive learning experiences, perhaps four or five sessions a week; unfortunately, this is not offered.

The resources available are useful, but they cannot replace the feeling of having your community behind you.

The refugees come to Akron, and they are lucky if they know one person who is already settled here. They are left to rebuild their communities in an unfamiliar environment. It can be a difficult and traumatic transition, and this orientation serves as the starting point of their new lives. With the help of the International Institute of Akron, there is hope for making Akron feel like home.