By Gabby Jonas

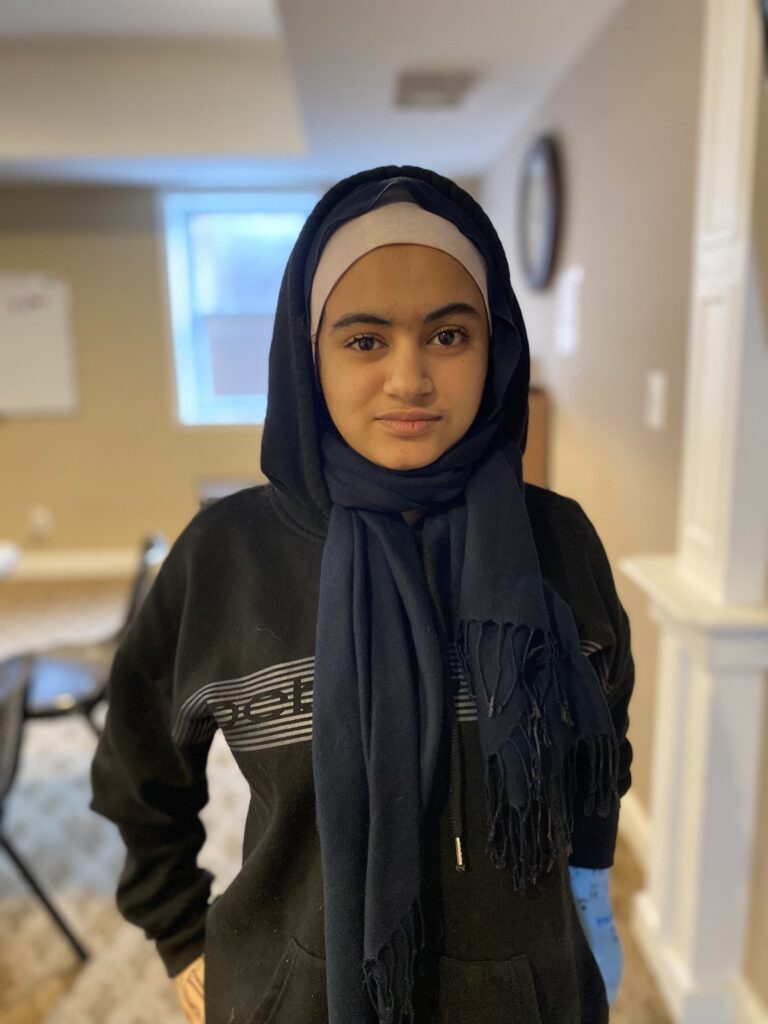

With a silk scarf, I covered my hair as I walked into the Islamic Society of Akron and Kent. I have never done this before and struggled as I used bobby pins and three hair ties to keep my hair in place. Removing my shoes as I walked in, I sat in a folded metal chair next to Sedna Alibraham, a 16-year-old refugee from Syria. Women covering their hair has always been a part of life. As she spoke softly with broken English, a young 10-year-old boy helped her translate her words, telling me the essence of what it means to be a proud Muslim, and how it’s made her proud to wear her hijab, a religious head scarf that covers her hair that embodies modesty. She remembers putting her hijab on for the first time in just first grade and feeling strong and womanly as her mother told her it was the best way to protect her modesty as a woman in this “new world.”

“I change myself when I wear the hijab,” she said.

She said it in a way that wasn’t negative but uplifting, as by putting on this black satin headscarf she was getting closer to her creator, a feeling that for her is unmatched. Though she barely remembers her home country of Syria – she left when she was six – the faint memory of fighting and bombs right outside her door is all that came to mind. Now living in Akron, Ohio she said she is grateful for the life America has given her. Her education, her family, and her freedom of religion.

“Everything [is] special. I’m always chilling with my friends [and] talking with them, spend[ing] time with my family, and going to the store,” Alibraham said.

For her, leading a life through her faith is what makes her the holiest version of herself. Every Saturday she goes to weekend school at the Islamic Society of Akron and Kent, a mosque that teaches children the Quran on the weekends, so the next generation of Muslims don’t forget who they really are, a religion and culture that dates back to the 7th century. Providing love and support for refugees like Alibraham at the Islamic Society of Akron and Kent makes the transition to Northeast Ohio easier.

On top of her own culture, she learns other languages as well. Something that women in Syria are not allowed to do for the sole purpose of not being a man. She told me her favorite thing to learn was about other cultures and languages, especially Spanish. A language that holds similar feelings on her tongue as speaking Arabic. But it’s the fact that her Saturday school provides her the ability to set a foundation in not only education but deepening her culture. By falling in love with her prophet Muhammad and God, Allah, she is choosing her religion, not just being taught it, an important fundamental in the Islamic religion.

Religion is the biggest thing. Whether you practice it or not, because that doesn’t just define who you are, but that defines your actions, it defines your explanations for your actions.

Sedna Alibraham

“[There is a] Blackstone on the side of it. Prophet Mohammed, he kissed the stone, and all Muslims want to follow him, so we can all go to heaven,” she said about the holiest place in her faith. The key that will allow her to become an angel herself someday.

She prays five times a day, waiting for the day that her lips touch the rock, too. Placing her right hand over her left on her chest she faces towards Kabba in Mecca, the most sacred site for Muslims that represents the metaphorical house of God. The same blackstone she hopes to kiss. She then places her hands on her temples, bringing them back down to her chest, bowing her knees on a beautiful woven rug such as red and gold and touching her forehead to the earth as a way of relaxing her body. When she does this she says “Bismillah,” the first words someone says before a verse in the Quran, finishing by thanking the angels on each side of her.

One of Alibraham’s teachers is Joud Matar, a 21-year-old refugee from Jordan. Like Alibraham, Matar came to the states at a young age. Her father, a refugee himself, only allows his family to speak Arabic, as he feels that is key for his children to not lose touch with their culture. But since he was on a business trip, sitting in her dad’s office in Kent, she spoke to me in English, jokingly saying that if he were home I’d need “good luck” translating what’s usually spoken in her house. She offered me a cup of both coffee and water. In the Islamic faith, if someone drinks a cup of water, that means the person is hungry, which meant she would know to feed me food without asking. A kind gesture that I politely declined.

She said her family visits Jordan almost every summer, seeing grandparents and other relatives that didn’t leave with them because of their fear of losing their culture and religion behind. In a world that seems to hold onto the new and negate the past, Matar said that is the last thing Muslims would do.

“Religion is the biggest thing. Whether you practice it or not, because that doesn’t just define who you are, but that defines your actions, it defines your explanations for your actions,” she said. “It’s the belief of God being closer to you than the veins in your skin. That God is literally with you in every single room that you walk in. God doesn’t need you to pray, you need to pray.”

As she spoke of wisdom beyond her years, she did so in a way that felt peaceful yet stern. Islam not only being the foundation of her people, but the foundation of herself.

“What makes Joud is religion. What makes Joud is being a Muslim. I would rather lose anything and everything except for my identity,” she said. “We have the privilege of living in a country where your religion is not just your religion, your religion is your identity. Your religion is what you present to the world.”

Growing up as a Jewish woman who is also close to their faith, I shared a deep appreciation for Joud speaking so intently about her own and what it meant to her. Wearing a gold necklace that wrote her name in Arabic, I sat across from her with a silver one that wrote my name in Hebrew. Two people depicted in the media to “hate” each other yet understanding one another with the same founding father of Abraham. One of the many things that make humans human — religion.

Though she feels fortunate to live in a country that allows her to freely express her religion, she doesn’t neglect the harsh reality of how many tend to think of her.

“It’s a sharp pain to your knee, or to your arm or to whatever you fall on,” she said. “But hearing ‘go back to where you came from,’ or ‘take it off,’ or ‘you’re oppressed’ or any of those things, that’s a sharp pain to the heart, that is not a sharp pain. Wounds can heal, but words cannot.”

Matar, a junior marketing student at Kent State University, took a religions class online, a credit class she chose to take before graduating. It was in this class her professor asked, “What is the first thing that comes to your mind when we say the word, Islam?” For Matar, the silence was defining. At that moment, she knew what they were thinking,

“Bombs, terrorists. I said, ISIS. I said, al Qaeda, I said, criminals. I said, 9/11,” she said. “I could hear his voice while he’s talking to me crack, and when I finished talking, I said, before you finish, I’m Muslim.”

At the end of the day, when you sit down, you and I put our pants on the same way.

Joud Matar

Although she believes that these worst versions of her religion shape the stereotypes that encompass her, she doesn’t let them stop her from her practice. Matar also wears the hijab with pride, showcasing a walking representation of her religion. It was her mother’s devotion to her faith that helped her find herself and this sense of pride for the tribe she had before she died of breast cancer. It was on her mother’s deathbed, unable to speak, only subtle noises, that showed Matar in her last moments the rawest form of being Muslim. She watched her mom make noise as her aunt read the Quran to her, confused by the sounds she made. She soon realized that it was because her aunt was mispronouncing words within the Quran, and her mother wanted her to say them correctly. A woman who memorized the Quran and was dedicated to it profoundly even in her last minutes of life, wanted the Quran said correctly. It was this action that inspired Matar to become the dedicated Muslim she is today.

Now, teaching children like Alibraham at the Islamic Society of Akron and Kent, she feels as if she is making a difference. Explaining to them that by learning to love one another that is,

“The most important part of Islam is the fact that me and you are the same under the eyes of God. You’re the exact same, whether you’re Christian, whether you’re Jewish, whether you’re Hindu, whether you’re Muslim. You are the same,” she said.

As I thanked her for her time, she smiled. Thanking me for taking the time to understand her. It was at that moment that I saw the beauty of people and how religion is something both refugees and immigrants share with many native-born Americans. Whether someone believes in the Quran, the Bible, the Torah or another form of religious practice,

“At the end of the day, when you sit down, you and I put our pants on the same way,” Matar said.